Machado de Assis

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Portuguese. (June 2024) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

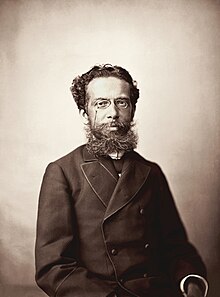

Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis (Portuguese: [ʒwɐˈkĩ maˈɾiɐ maˈʃadu d͡ʒ(i) aˈsis]), often known by his surnames as Machado de Assis, Machado, or Bruxo do Cosme Velho[1] (21 June 1839 – 29 September 1908), was a pioneer Brazilian novelist, poet, playwright and short story writer, widely regarded as the greatest writer of Brazilian literature.[2][3][4] In 1897, he founded and became the first President of the Brazilian Academy of Letters. He was multilingual, having taught himself French, English, German and Greek later in life.

Born in Morro do Livramento, Rio de Janeiro, from a poor family, he was the grandson of freed slaves in a country where slavery would not be fully abolished until 49 years later. He barely studied in public schools and never attended university. With only his own intellect and autodidactism to rely on, he struggled to rise socially. To do so, he took several public positions, passing through the Ministry of Agriculture, Trade and Public Works, and achieving early fame in newspapers where he first published his poetry and chronicles.

Machado's work shaped the realist movement in Brazil. He became known for his wit and his eye-opening critiques of society.[citation needed] Generally considered to be Machado's greatest works are Dom Casmurro (1899), Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas ("Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas", also translated as Epitaph of a Small Winner) and Quincas Borba (also known in English as Philosopher or Dog?). In 1893, he published "A Missa do Galo" ("Midnight Mass"), often considered to be the greatest short story in Brazilian literature.[5]

Biography

[edit]Birth and adolescence

[edit]

Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis was born on 21 June 1839 in Rio de Janeiro, then capital of the Empire of Brazil.[6][7][8] His parents were Francisco José de Assis, a wall painter, the son of freed slaves,[9] and Maria Leopoldina da Câmara Machado, a Portuguese washerwoman from the Azores.[7][10] He was born in Livramento country house, owned by Dona Maria José de Mendonça Barroso Pereira, widow of senator Bento Barroso Pereira, who protected his parents and allowed them to live with her.[6][7] Dona Maria José became Joaquim's godmother; her brother-in-law, commendator Joaquim Alberto de Sousa da Silveira, was his godfather, and both were paid homage by giving their names to the baby.[6][7] Machado had a sister who died young.[8] Joaquim studied in a public school, but was not a good student.[6] While helping to serve masses, he met Father Silveira Sarmento, who became his Latin teacher and also a good friend.[6][7]

When Joaquim was ten years old, his mother died, and his father took him along as he moved to São Cristóvão. Francisco de Assis met Maria Inês da Silva, and they married in 1854.[6][7][8] Joaquim had classes in a school for girls only, thanks to his stepmother who worked there making candies. At night he learned French with an immigrant baker.[6] In his adolescence, he met Francisco de Paulo Brito, who owned a bookstore, a newspaper and typography.[6] On 12 January 1855, Francisco de Paula published the poem Ela ("Her") written by Joaquim, then 15 years old, in the newspaper Marmota Fluminense.[6][7][8] In the following year, he was hired as typographer's apprentice in the Imprensa Oficial (the Official Press, charged with the publication of Government measures), where he was encouraged as a writer by Manuel Antônio de Almeida, the newspaper's director and also a novelist.[6] There he also met Francisco Otaviano, journalist and later liberal senator, and Quintino Bocaiuva, who decades later would become known for his role as a republican orator.[11]

Early career and education

[edit]

Francisco Otaviano hired Machado to work on the newspaper Correio Mercantil as a proofreader in 1858.[8][11] He continued to write for the Marmota Fluminense and also for several other newspapers, but he did not earn much and had a humble life.[8][11] As he did not live with his father anymore, it was common for him to eat only once a day for lack of money.[11]

Around this time, he became a friend of the writer and liberal politician José de Alencar, who taught him English. From English literature, he was influenced by Laurence Sterne, William Shakespeare, Lord Byron and Jonathan Swift. He learned German years later and in his old age, Greek.[11] He was invited by Bocaiúva to work at his newspaper Diário do Rio de Janeiro in 1860.[7][12] Machado had a passion for theater and wrote several plays for a short time; his friend Bocaiúva concluded: "Your works are meant to be read and not played."[12] He gained some notability and began to sign his writings as J. M. Machado de Assis, the way he would be known for posterity: Machado de Assis.[12] He established himself in advanced Liberal Party circles by taking stands in defense of religious freedom and Ernest Renan's controversial Life of Jesus while attacking the venality of the clergy.[13]

His father Francisco de Assis died in 1864. Machado learned of his father's death through acquaintances. He dedicated his compilation of poems called "Crisálidas" to his father: "To the Memory of Francisco José de Assis and Maria Leopoldina Machado de Assis, my Parents."[14] With the Liberal Party's ascension to power about that time, Machado thought he might receive a patronage position that would help him improve his life. To his surprise, aid came from the Emperor Dom Pedro II, who hired him as director-assistant in the Diário Oficial in 1867, and knighted him as an honor.[14] In 1888 Machado was made an officer of the Order of the Rose.[8]

Marriage and family

[edit]In 1868 Machado met the Portuguese Carolina Augusta Xavier de Novais, five years older than he was.[14] She was the sister of his colleague Faustino Xavier de Novais, for whom he worked on the magazine O Futuro.[8][11] Machado had a stammer and was extremely shy, short and lean. He was also very intelligent and well learned.[14] He married Carolina on 12 November 1869; although her parents, Miguel and Adelaide, and her siblings disapproved because Machado was of African descent and she was a white woman.[7][14] They had no children.[15]

Literature

[edit]

Machado managed to rise in his bureaucratic career, first in the Agriculture Department. Three years later, he became the head of a section in it.[7][16] He published two poetry books: Falenas, in 1870, and Americanas, in 1875.[16] Their weak reception made him explore other literary genres.

He wrote five romantic novels: Ressurreição, A Mão e a Luva, Helena and Iaiá Garcia.[16] The books were a success with the public, but literary critics considered them mediocre.[16] Machado suffered repeated attacks of epilepsy, apparently related to hearing of the death of his old friend José de Alencar. He was left melancholic, pessimistic and fixed on death.[17] His next book, marked by "a skeptical and realistic tone": Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas (Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas, also translated as Epitaph of a Small Winner), is widely considered a masterpiece.[18] By the end of the 1880s, Machado had gained wide renown as a writer.[8]

Although he was opposed to slavery, he never spoke against it in public.[16][19] He avoided discussing politics.[18][19] He was criticized by the abolitionist José do Patrocínio and by the writer Lima Barreto for staying away from politics, especially the cause of abolition.[1][19] He was also criticized by them for having married a white woman.[1] Machado was caught by surprise with the monarchy overthrown on 15 November 1889.[18] Machado had no sympathy towards republicanism,[18] as he considered himself a liberal monarchist[20] and venerated Pedro II, whom he perceived as "a humble, honest, well-learned and patriotic man, who knew how to make of a throne a chair [for his simplicity], without diminishing its greatness and respect."[21] When a commission went to the public office where he worked to remove the picture of the former emperor, the shy Machado defied them: "The picture got in here by an order and it shall leave only by another order."[18]

The birth of the Brazilian republic made Machado become more critical and an observer of the Brazilian society of his time.[22] From then on, he wrote "not only the greatest novels of his time, but the greatest of all time of Brazilian literature."[20] Works such as Quincas Borba (Philosopher or Dog?) (1891), Dom Casmurro (1899), Esaú e Jacó (1904) and Memorial de Aires (1908), considered masterpieces,[20] were successes with both critics and the public.[23] In 1893 he published "A Missa do Galo" ("Midnight Mass"), considered his greatest short story.[24]

Later years

[edit]

Machado de Assis, along with fellow monarchists such as Joaquim Nabuco, Manuel de Oliveira Lima, Afonso Celso, Viscount of Ouro Preto and Alfredo d'Escragnolle Taunay, and other writers and intellectuals, founded the Brazilian Academy of Letters. He was its first president, from 1897 to 1908, when he died.[1][8] For many years, he requested that the government grant a proper headquarters to the Academy, which he managed to obtain in 1905.[25] In 1902 he was transferred to the accountancy's directing board of the Ministry of Industry.[25]

His wife Carolina Novais died on 20 October 1904, after 35 years of a "perfect married life".[1][25][26] Feeling depressed and lonely, Machado died on 29 September 1908.[15]

Narrative style

[edit]

Machado's style is unique, and several literary critics have tried to describe it since 1897.[27] He is considered by many the greatest Brazilian writer of all time, and one of the world's greatest novelists and short story writers. His chronicles do not share the same status. His poems are often misunderstood for the use of crude terms, sometimes associated to the pessimist style of Augusto dos Anjos, another Brazilian writer. Machado de Assis was included on American literary critic Harold Bloom's list of the greatest 100 geniuses of literature, alongside writers such as Dante, Shakespeare and Cervantes. Bloom considers him the greatest black writer in Western literature; although, in Brazil, Machado is perceived as a Pardo.

His works have been studied by critics in various countries of the world, such as Giuseppe Alpi (Italy), Lourdes Andreassi (Portugal), Albert Bagby Jr. (US), Abel Barros Baptista (Portugal), Hennio Morgan Birchal (Brazil), Edoardo Bizzarri (Italy), Jean-Michel Massa (France), Helen Caldwell (US), John Gledson (England), Adrien Delpech (France), Albert Dessau (Germany), Paul B. Dixon (US), Keith Ellis (US), Edith Fowke (Canada), Anatole France (France), Richard Graham (US), Pierre Hourcade (France), David Jackson (US), G. Reginald Daniel (US), Linda Murphy Kelley (US), John C. Kinnear, Alfred Mac Adam (US), Victor Orban (France), Daphne Patai (US), Houwens Post (Italy), Samuel Putnam (US), John Hyde Schmitt, Tony Tanner (England), Jack E. Tomlins (US), Carmelo Virgillo (US), Dieter Woll (Germany), August Willemsen (Netherlands) and Susan Sontag (US).[28]

Critics are divided as to the nature of Machado de Assis's writing. Some, such as Abel Barros Baptista, classify Machado as a staunch anti-realist, and argue that his writing attacks Realism, aiming to negate the possibility of representation or the existence of a meaningful objective reality. Realist critics such as John Gledson are more likely to regard Machado's work as a faithful description of Brazilian reality—but one executed with daring innovative technique. In light of Machado's own statements, Daniel argues that Machado's novels represent a growing sophistication and daring in maintaining a dialogue between the aesthetic subjectivism of Romanticism (and its offshoots) and the aesthetic objectivism of Realism-Naturalism. Accordingly, Machado's earlier novels have more in common with a hybrid mid-19th-century current often referred to as "Romantic Realism."[29] In addition, his later novels have more in common with another late 19th-century hybrid: literary Impressionism. Historians such as Sidney Chalhoub argue that Machado's prose constitutes an exposé of the social, political and economic dysfunction of late Imperial Brazil. Critics agree on how he used innovative techniques to reveal the contradictions of his society. Roberto Schwarz points out that Machado's innovations in prose narrative are used to expose the hypocrisies, contradictions, and dysfunction of 19th-century Brazil.[30] Schwarz, argues that Machado inverts many narrative and intellectual conventions to reveal the pernicious ends to which they are used. Thus we see critics reinterpret Machado according to their own designs or their perception of how best to validate him for their own historical moment. Regardless, his incisive prose shines through, able to communicate with readers from different times and places, conveying his ironic and yet tender sense of what we, as human beings, are.[29]

Machado's literary style has inspired many Brazilian writers. His works have been adapted to television, theater, and cinema. In 1975 the Comissão Machado de Assis ("Machado de Assis Commission"), organized by the Brazilian Ministry of Education and Culture, organized and published critical editions of Machado's works, in 15 volumes. His main works have been translated into many languages. Great 20th-century writers such as Salman Rushdie, Cabrera Infante and Carlos Fuentes, as well as the American film director Woody Allen, have expressed their enthusiasm for his fiction.[31] Despite the efforts and patronage of such well-known intellectuals as Susan Sontag, Harold Bloom, and Elizabeth Hardwick, Machado's books—the most famous of which are available in English in multiple translations—have never achieved large sales in the English-speaking world and he continues to be relatively unknown, even by comparison with other Latin American writers.

In his works, Machado appeals directly to the reader, breaking the so-called fourth wall.[citation needed]

List of works

[edit]

Novels

[edit]- 1872 – Ressurreição (Resurrection)[32]

- 1874 – A Mão e a Luva (The Hand and the Glove)

- 1876 – Helena

- 1878 – Iaiá Garcia

- 1881 – Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas (The Posthumous Memoirs of Bras Cubas, also known in English as Epitaph of a Small Winner)

- 1891 – Quincas Borba (also known in English as Philosopher or Dog?)

- 1899 – Dom Casmurro

- 1904 – Esaú e Jacó (Esau and Jacob)

- 1908 – Memorial de Aires (Counselor Ayres' Memorial)

Novellas

[edit]- 1881 – O alienista (The Psychiatrist, or The Alienist)

- 1886 – Casa velha (published as a book in 1944)

Plays

[edit]- 1860 – Hoje avental, amanhã luva

- 1861 – Desencantos

- 1863 – O caminho da porta and O protocolo (two plays)

- 1864 – Quase ministro

- 1865 – As Forcas Caudinas (published 1956)

- 1866 – Os deuses de casaca

- 1878 – A Sonâmbula, Antes da Missa and O bote de rapé (three short plays)

- 1881 – Tu, só tu, puro amor

- 1896 – Não consultes médico

- 1906 – Lição de botânica

Poetry

[edit]- 1864 – Crisálidas

- 1870 – Falenas (including the dramatic poem Uma ode de anacreonte)

- 1875 – Americanas

- 1901 – Ocidentais

- 1901 – Poesias Completas (complete poetry)

Short-story collections

[edit]- 1870 – Contos Fluminenses

- 1873 – Histórias da meia-noite

- 1882 – Papéis avulsos (including "O alienista")

- 1884 – Histórias sem data

- 1896 – Várias histórias

- 1899 – Páginas recolhidas (including "A Missa do Galo" and "The Case of the Stick")

- 1906 – Relíquias de Casa Velha

Translations

[edit]- 1861 – Queda que as mulheres têm para os tolos, from the original De l'amour des femmes pour les sots, by Victor Hénaux

- 1865 – Suplício de uma mulher, from the original Le supplice d'une femme, by Émile de Girardin

- 1866 – Os Trabalhadores do Mar, from the original Les Travailleurs de la mer, by Victor Hugo

- 1870 – Oliver Twist, from the original Oliver Twist; or, the Parish Boy's Progress, by Charles Dickens[33]

- 1883 – O Corvo, from The Raven, a famous poem by Edgar Allan Poe

Posthumous

[edit]- 1910 – Teatro Coligido (collected plays)

- 1910 – Crítica

- 1914 – A Semana (collection of articles)

- 1921 – Outras Relíquias (collection of short stories)

- 1921 – Páginas Escolhidas (collection of short stories)

- 1932 – Novas Relíquias (collection of short stories)

- 1937 – Crônicas (articles)

- 1937 – Crítica Literária

- 1937 – Crítica Teatral

- 1937 – Histórias Românticas

- 1939 – Páginas Esquecidas

- 1944 – Casa Velha

- 1956 – Diálogos e Reflexões de um Relojoeiro

- 1958 – Crônicas de Lélio

Collected works

There are several published "Complete Works" of Machado de Assis:

- 1920 – Obras Completas. Rio de Janeiro: Livraria Garnier (20 vols.)

- 1962 – Obras Completas. Rio de Janeiro: W.M. Jackson (31 vols.)

- 1997 – Obras Completas. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Globo (31 vols.)

- 2006 – Obras Completas. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Aguilar (3 vols.)

Works in English translation

- 1921 – Brazilian Tales. Boston: The Four Seas Company (London: Dodo Press, 2007).

- 1952 – Epitaph of a Small Winner. New York: Noonday Press (London: Hogarth Press, 1985; republished as The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas: A Novel. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997; Epitaph of a Small Winner. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2008; UK: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2008).

- 1953 – Dom Casmurro: A Novel. New York: Noonday Press (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966; republished as Dom Casmurro. Lord Taciturn. London: Peter Owen, 1992; Dom Casmurro: A Novel. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

- 1954 – Philosopher or Dog? New York: Avon Books (republished as The Heritage of Quincas Borba. New York: W.H. Allen, 1957; New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1992; republished as Quincas Borba: A Novel. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998).

- 1963 – The Psychiatrist, and Other Stories. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- 1965 – Esau and Jacob. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- 1970 – The Hand & the Glove. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

- 1972 – Counselor Ayres' Memorial. Berkeley: University of California Press (republished as The Wager: Aires' Journal. London: Peter Owen, 1990; also republished as The Wager, 2005).

- 1976 – Yayá Garcia: A Novel. London: Peter Owen (republished as Iaiá Garcia. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1977).

- 1977 – The Devil's Church and Other Stories. Austin: University of Texas Press (New York: HarperCollins Publishers Ltd, 1987).

- 1984 – Helena: A Novel. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- 2008 – A Chapter of Hats and Other Stories. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- 2012 – The Alienist. New York: Melville House Publishing.

- 2013 – Resurrection. Pennsylvania: Latin American Literary Review Press.

- 2013 – The Alienist and Other Stories of Nineteenth-century Brazil. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

- 2014 – Ex Cathedra: Stories by Machado de Assis — Bilingual Edition. Hanover, Conn.: New London Librarium.

- 2016 – Miss Dollar: Stories by Machado de Assis — Bilingual Edition. Hanover, Conn.: New London Librarium.

- 2018 – Trio in A-Minor: Five Stories by Machado de Assis—Bilingual Edition. Hanover, Conn.: New London Librarium.

- 2018 – The Collected Stories of Machado de Assis. New York : Liveright & Company.

- 2018 – Good Days!: The Bons Dias! Chronicles of Machado de Assis (1888-1889) — Bilingual Edition. Hanover, Conn.: New London Librarium.

Honours

[edit]

- Founding member of the Brazilian Academy of Letters (1896–1908).

- President of the Brazilian Academy of Letters (1897–1908).

Honours

[edit] Empire of Brazil: Knight of the Order of the Rose (1867).

Empire of Brazil: Knight of the Order of the Rose (1867). Empire of Brazil: Officer of the Order of the Rose (1888).

Empire of Brazil: Officer of the Order of the Rose (1888).

Tribute

[edit]On 21 June 2017, Google celebrated his 178th birthday with a Google Doodle.[34]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Vainfas, p. 505.

- ^ Candido; Antonio (1970), Vários escritos. São Paulo: Duas Cidades. p. 18.

- ^ Caldwell, Helen (1970), Machado de Assis: The Brazilian Master and his Novels. Berkeley, Los Angeles/London: University of California Press.

- ^ Fernandez, Oscar, "Machado de Assis: The Brazilian Master and His Novels", The Modern Language Journal, Vol. 55, No. 4 (April 1971), pp. 255–256.

- ^ Scarano, p. 775.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Scarano, p. 766.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Vainfas, p. 504.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Enciclopédia Barsa, p. 267.

- ^ "Biografia de Machado de Assis" [Machado de Assis’ biography]. Livraria Pública (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on 12 October 2019.

- ^ Scarano, p. 765.

- ^ a b c d e f Scarano, p. 767.

- ^ a b c Scarano, p. 769.

- ^ Borges, Dain (2016). "Mockery and Piety in Eça de Queirós and Machado de Assis". Revista de Estudos Literários. 6: 97.

- ^ a b c d e Scarano, p. 770.

- ^ a b Scarano, p. 780.

- ^ a b c d e Scarano, p. 773.

- ^ Scarano, pp. 774–774.

- ^ a b c d e Scarano, p. 774.

- ^ a b c Daniel, pp. 61–152.

- ^ a b c Bueno, p. 310.

- ^ Vainfas, p. 201: "Machado de Assis, porém, soube definí-lo em rápidos traços: um homem lhano, probo, instruído, patriota, que soube fazer do sólio uma poltrona, sem lhe diminuir a grandeza e a consideração."

- ^ Bueno, p. 311.

- ^ Scarano, p. 777.

- ^ Scarano, p. 775.

- ^ a b c Scarano, p. 778.

- ^ Enciclopédia Barsa, p. 267: "vida conjugal perfeita".

- ^ Romero, Silvio (1897), Machado de Assis: Estudo Comparativo da Literatura Brasileira, Rio de Janeiro: Laemmert.

- ^ Susan Sontag, Foreword. Epitaph of a Small Winner. By J. M. Machado de Assis. Trans. William Grossman. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1990. xi–xxiv.

- ^ a b Daniel, pp. 190–237.

- ^ Daniel, pp. 153–218.

- ^ Rocha, João Cezar de Castro (2006). "Introduction" (PDF). Portuguese Literature and Cultural Studies. 13/14: xxiv. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2008.

- ^ "Machado de Assis - Vida e Obra". machado.mec.gov.br. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ Machado's translation originally appeared in serial form in the newspaper Jornal da Tarde, from 24 April to 23 August 1870.

- ^ "Machado de Assis' 178th Birthday". Google. 21 June 2017. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023.

References

[edit]- Bueno, Eduardo (2003). Brasil: Uma História. 1ª ed. São Paulo: Ática. (in Portuguese)

- Encilopédia Barsa (1987). Volume 10: "Judô – Mercúrio". Rio de Janeiro: Encyclopædia Britannica do Brasil. (in Portuguese)

- Scarano, Júlia Maria Leonor (1969). Grandes Personagens da Nossa História. São Paulo: Abril Cultural. (in Portuguese)

- Vainfas, Ronaldo (2002). Dicionário do Brasil Imperial. Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva. (in Portuguese)

Further reading

[edit]- Abreu, Modesto de (1939). Machado de Assis. Rio de Janeiro: Norte.

- Andrade, Mário (1943). Aspectos da Literatura Brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Americ. Ed.

- Aranha, Graça (1923). Machado de Assis e Joaquim Nabuco: Comentários e Notas à Correspondência. São Paulo: Monteiro Lobato.

- Barreto Filho (1947). Introdução a Machado de Assis. Rio de Janeiro: Agir.

- Bettencourt Machado, José (1962). Machado of Brazil, the Life and Times of Machado de Assis, Brazil's Greatest Novelist. New York: Charles Frank Publications.

- Bosi, Alfredo. (Organizador) Machado de Assis. São Paulo: Editora Atica, 1982.

- Bosi, Alfredo (2000). Machado de Assis: O Enigma do Olhar. São Paulo: Ática.

- Broca, Brito (1957). Machado de Assis e a Política. Rio de Janeiro: Organização Simões Editora.

- Chalhoub, Sidney (2003). Machado de Assis, Historiador. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

- Cheney, et al. (editors) (2014) Ex Cathedra: Stories by Machado de Assis--Bilingual Edition. Hanover, CT:New London Librarium ISBN 978-0985628482

- Corção, Gustavo (1956). Machado de Assis. Rio de Janeiro: Agir.

- Coutinho, Afrânio (1959). A Filosofia de Machado de Assis e Outros Ensaios. Rio de Janeiro: São José.

- Dantas, Júlio (1940). Machado de Assis. Lisboa: Academia das Ciências.

- Dixon, Paul B. (1989). Retired Dreams: Dom Casmurro, Myth and Modernity. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press.

- Faoro, Raimundo (1974). Machado de Assis: Pirâmide e o Trapézio. São Paulo: Cia. Ed. Nacional.

- Fitz, Earl E. (1989). Machado de Assis. Boston: Twayne Publishers.

- Gledson, John (1984). The Deceptive Realism of Machado de Assis. Liverpool: Francis Cairns.

- Gledson, John (1986). Machado de Assis: Ficção e História. Rio de Janeiro: Paz & Terra.

- Goldberg, Isaac (1922). "Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis." In: Brazilian Literature. New York: Alfred A. Knoff, pp. 142–164.

- Gomes, Eugênio (1976). Influências Inglesas em Machado de Assis. Rio de Janeiro: Pallas; Brasília: INL.

- Graham, Richard (ed.). Machado de Assis: Reflections on a Brazilian Master Writer. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1999.

- Lima, Alceu Amoroso (1941). Três Ensaios sobre Machado de Assis. Belo Horizonte: Paulo & Bruhm.

- Magalhães Jr, Raimundo (1981). Vida e Obra de Machado de Assis. Rio de Janeiro/Brasília: Civilização Brasileira/INL.

- Maia Neto, José Raimundo (1984). Machado de Assis, the Brazilian Pyrrhonian. West Lafayette, Ind.: Purdue University Press.

- Massa, Jean-Michel (1971). A Juventude de Machado de Assis. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira.

- Merquior, José Guilherme (1971). "Machado de Assis e a Prosa Impressionista." In: De Anchieta a Euclides; Breve História da Literatura Brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio, pp. 150–201.

- Meyer, Augusto (1935). Machado de Assis. Porto Alegre: Globo.

- Meyer, Augusto (1958). Machado de Assis 1935–1958. Rio de Janeiro: Livraria São José.

- Montello, Jesué (1998). Os Inimigos de Machado de Assis. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Nova Fronteira.

- Nunes, Maria Luisa (1983). The Craft of an Absolute Winner: Characterization and Narratology in the Novels of Machado de Assis. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press.

- Paes, José Paulo. (1985). Gregos e Baianos: Ensaios. São Paulo: Brasiliense.

- Pereira, Astrogildo (1944). Interpretação. Rio de Janeiro: Casa do Estudante do Brasil.

- Miguel-Pereira, Lúcia (1936). Machado de Assis: Estudo Critíco e Biográfico. São Paulo: Cia. Ed. Nacional.

- Schwarz, Roberto (2000). Ao Vencedor as Batatas. São Paulo: Duas Cidades/Editora34.

- Schwarz, Roberto (1997). Duas Meninas. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

- Schwarz, Roberto (1990). Um Mestre na Periferia do Capitalismo. São Paulo: Duas Cidades. Trans. as A Master on the Periphery of Capitalism. Trans. and intro. John Gledson. Durham: Duke UP, 2001.

- Sontag, Susan (2001). "Afterlives: The Case of Machado de Assis". In Where the Stress Falls. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Taylor, David (2002). "Wry Modernist of Brazil's Past." Américas, Nov.-Dec., issue. Washington, DC.

- Veríssimo, José (1916). História da Literatura Brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Livrarias Aillaud & Bertrand.

External links

[edit]- (in Portuguese) Machado de Assis at Brasialiana, University of São Paulo (digitalized first editions of all the books in PDF)

- (in Portuguese) Complete Works of Machado de Assis – Brazilian Ministry of Education

- (in Portuguese) MetaLibri Digital Library

- Petri Liukkonen. "Machado de Assis". Books and Writers.

- (in Portuguese) Machado de Assis a literary biography.

- (in Portuguese) Books of Machado de Assis in Biblioteca Virtual do Estudante de Língua Portuguesa.

- Manuscrito de Machado de Assis – Handwritten pieces

- Espaço Machado de Assis

- João Cezar de Castro Rocha, "Introduction: Machado de Assis, the Location of an Author"

- Works by Machado de Assis at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Machado de Assis at the Internet Archive

- Works by Machado de Assis at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Machado de Assis

- 1839 births

- 1908 deaths

- Brazilian monarchists

- Brazilian male novelists

- 19th-century Brazilian dramatists and playwrights

- Brazilian male dramatists and playwrights

- 19th-century Brazilian poets

- Brazilian male poets

- Brazilian male short story writers

- Brazilian translators

- Members of the Brazilian Academy of Letters

- 19th-century Brazilian novelists

- 20th-century Brazilian novelists

- Brazilian people of Azorean descent

- Writers from Rio de Janeiro (city)

- Portuguese-language writers

- Translators to Portuguese

- 19th-century Brazilian short story writers

- Brazilian people of African descent

- 19th-century Brazilian male writers

- Afro-Brazilian people